In love thanks to your microbes

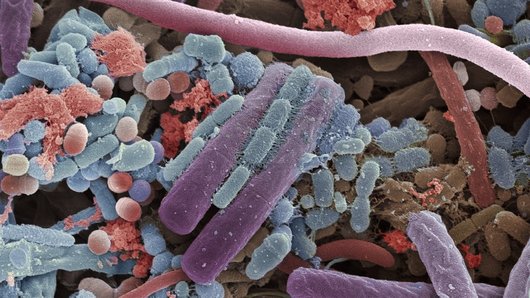

They mainly exert this influence through body odour. Our body odour plays an important and for the most part unconscious role in the choice of partner. In mammals (which includes humans), body odour is determined by the smell of sweat. Sweat itself has no odour; it is the skin bacteria living in our sweat glands that make it smell. One of the compounds added by these bacteria is AND, which causes a strong reaction in the part of the brain that is key for sexual arousal.

The composition of our sweat bacteria and therefore our body odour is different for everyone. Studies show that we subconsciously choose a bodily odour that is complementary to ours. In other words, we choose a partner with a different bacterial composition, ensuring our offspring will have a more diverse and therefore healthier microbiome.