Bacterial vaginosis

The lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus crispatus is a natural resident of the vagina. It produces lactic acid, contributing to an acid vaginal environment. This acidity is important, as pathogenic bacteria generally do not like a low pH. However, the vagina does not always have a low pH. An elevated pH is sometimes accompanied by bacterial vaginosis , indicating that the vaginal microbiome is out of balance. A large diversity of harmful bacteria suppresses the Lactobacillus, adversely affecting the protective mucous layer of the vagina. This situation can cause irritation and an unpleasant smell. Bacterial vaginosis also heightens the risk of acquiring sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and increases the chances of premature births.

A different layer

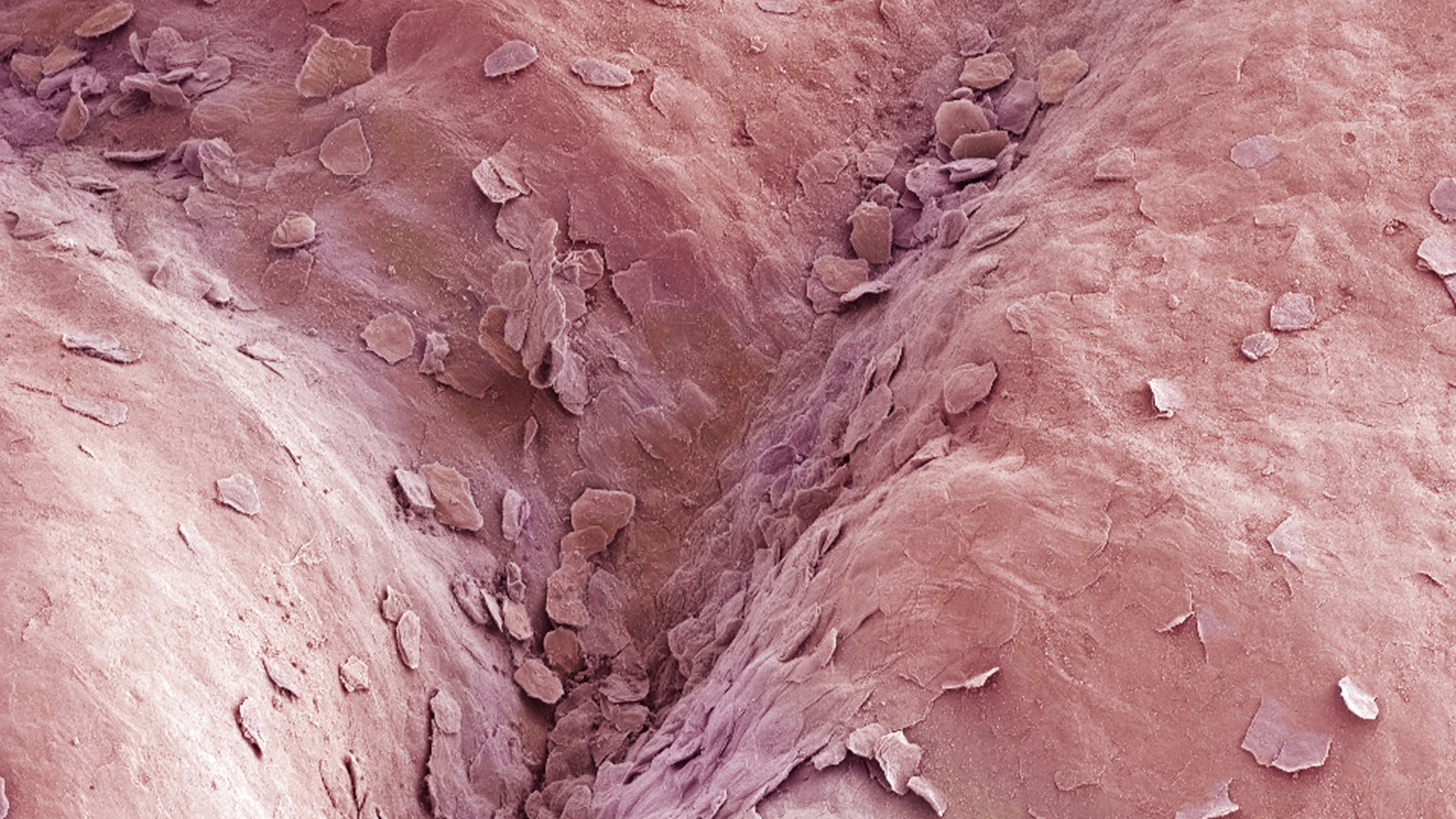

An important question is how exactly bacterial vaginosis develops. Is Lactobacillus crispatus suppressed by other types of bacteria, or do changing conditions in the vagina disrupt the dominance of this bacteria and prevent it from keeping the pH low? Perhaps the Lactobacillus species itself changes, inhibiting its capacity to dominate. Micropia professor Remco Kort investigated this process in his research group at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam by comparing dozens of Lactobacillus crispatus strains that came from both healthy and disbalanced vaginas. His study, which has been published in the Microbiome journal, shows that L. crispatus strains from a healthy vagina have more trouble creating a ‘different layer’ – the outer membrane.

A new probiotic?

The external layer of a bacterial cell, the outer membrane, is a hard cell wall with polysaccharide components. By modifying these sugars, the cell may no longer be detectable by the human immune system. Another effect of this ‘different layer’ may be that the bacterial cell can no longer be attacked by viruses that kill the bacteria (known as bacteriophages). This theory may explain why only L. crispatus strains with this property can still be present in the case of bacterial vaginosis (with an enhanced activity of the immune system or the presence of certain bacteriophages). These interesting hypotheses all have yet to be investigated. Down the line, this discovery could contribute to the selection of probiotic bacteria with this special property that can combat the common condition of bacterial vaginosis. In any event, many commonly used methods turn out to be ineffective, including antibiotics or vaginal douches with lactic acid.

Source: microbiomejournal , naturemicrobiologycommunity , nrc .