Growing problem

Antibiotics resistance is a growing problem. A lack of new antibiotics, as well as incorrect use of existing antibiotics in human healthcare and livestock breeding, is leading to ever more multi-resistant bacteria such as MRSA. Every year these bacteria cause more than 700,000 deaths worldwide. It often occurs that disease-causing bacteria that are not resistant to an antibiotic course of treatment nonetheless manage to survive, and this increases the problem even more. Groningen-based and American microbiologists conducted research into the reasons for this and made an unexpected discovery.

The experiment

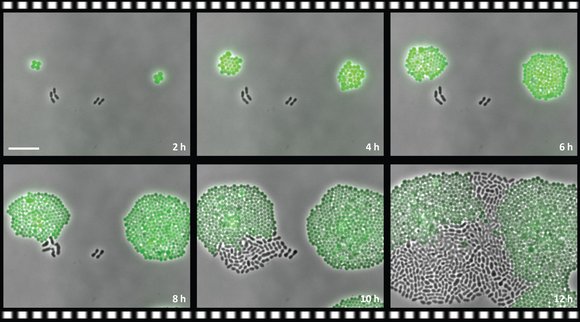

In their experiments the researchers used the antibiotic chloramphenicol. They administered this to a mix of resistant Staphylococcus bacteria and non-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Staphylococcus were given a green fluorescent protein to distinguish them from the S. pneumoniae. After administering the antibiotic, the team discovered something strange. The unsusceptible Staphylococcus continued to increase in numbers (as expected), but the Streptococcus, which were not expected to survive the antibiotic, remained steady in number. Over the course of time they began to multiply again and in a few cases they even out-competed the Staphylococcus.

The resistant Staphylococcus (green) increases in number during the antibiotic course of treatment. The non-resistant S. pneumoniae (black) does not disappear, however, but survives and in the course of time may even become dominant (photo: Sorg et al. RUG/UC SD).

Absorption

It turned out that these remarkable observations could be explained by the way in which the Staphylococcus breaks down the antibiotic. The bacterium has a gene that can render chloramphenicol harmless, but only within its cell. So the bacterium must first absorb the antibiotic from its surroundings in order to break it down. But it turns out to be so good at this job that during a course of treatment with chloramphenicol it absorbs just about all antibiotics and so no antibiotics then remain. This is, of course, a very useful state of affairs for the S. pneumoniae. By waiting until the course of treatment was over and by not wasting any energy by reproducing, or even by absorbing a resistance gene from the environment, S. pneumoniae was able – counter to expectations – to survive and sometimes even to become stronger. And this bacterium is certainly not the only one that makes use of another species’ resistance.

Personalized medicine

The discovery by the researchers in Groningen and America provides a new perspective on how microbes can endanger antibiotic therapies. According to the researchers it is thus important that an antibiotic course of treatment becomes a form of ‘personalized medicine’, in which not only the disease-causing microbe is tested for resistance, but the entire microbiome of the organ needing to be healed.

Source: PLOS