islands of plastic

Large islands of plastic form a thick mush which floats around on the surface, severely disrupting the ecosystem. Pieces of plastic can suffocate marine animals or clog up their digestive tracts. In addition to these plastic islands, the ocean is filled with so-called microplastics. Wave action and currents gradually break larger pieces of plastic down into microscopic particles. As they end up in the tissues of marine animals, these particles accumulate in the food chain. However, it seems that microbes have found a way to adapt to this situation.

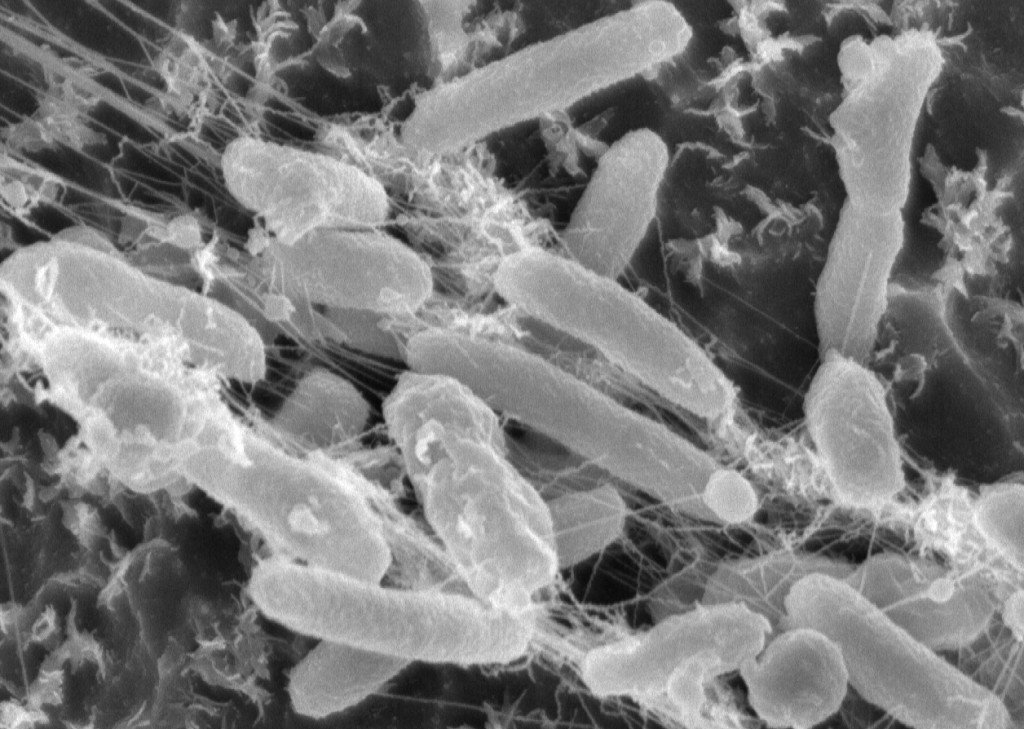

Ideonella sakaiensis binds to plastic by making sticky threads, which it uses to glue itself down.

too cold

Japanese researchers have discovered a bacterium that breaks down PET. PET (or polyethylene terephthalate as it is officially known) is widely used in the manufacture of plastic bottles and packaging. The bacterial species Ideonella sakaiensis secretes enzymes that liquefy the PET, which the bacterium can then easily absorb. In this way, these bacteria can break down a PET bottle in less than six weeks, at a temperature of 30°C. The seas and oceans rarely reach such a high temperature. As a result, it takes the bacteria longer to break down a bottle in the natural environment. Researchers are still trying to find out how long exactly.

spreading out

Science is eager to use this new species to deal with the plastic problem. For the time being, there are two ways in which these bacteria could be used. For instance, the researchers could allow Ideonella sakaiensis to break down plastic naturally. The bacteria would then spread out into all of the contaminated areas. While this option is inexpensive, logic indicates that it would take longer to achieve the desired result.

A second option would be to grow the bacteria in the laboratory, then distribute them artificially. While it is a lot faster, this approach is also associated with a lower chance of success. Scientists fear that the bacteria would not survive the transition from the laboratory to the natural environment. Thus, the use of this exceptional bacterium is still in its infancy. Fortunately, there is a great deal of interest in putting Ideonella sakaiensis to work in combating the world’s plastic problem.

Source:

Science