Lichens are a symbiosis between a fungus, a yeast and a green alga or blue-green alga. Although these organisms are microbes, they are easily visible to the naked eye in this symbiosis. There are around 650 different types of lichens in the Netherlands, half of which are under threat. Lichens can be found outdoors on trees and stones, in the sand as well as on walls and roofs.

Lichens are a symbiosis between a fungus, a yeast and a green alga or blue-green alga. Although these organisms are microbes, they are easily visible to the naked eye in this symbiosis. There are around 650 different types of lichens in the Netherlands, half of which are under threat. Lichens can be found outdoors on trees and stones, in the sand as well as on walls and roofs.

Smart division of tasks

All parties benefit from the collaboration between fungi, yeasts and algae: it is a so-called mutualistic symbiosis. The fungus creates the outer shell of the lichen, storing water and minerals to be used by its alga partner. On its part, the yeast produces antibodies to stave off competitors. In turn, the alga provides its partners with sugars. Just as plants, algae are able to turn sunlight into sugars via photosynthesis. While the alga uses some of the sugar for its own needs, it hands over another part to the fungus and the yeast. As the alga has to share its nutrients, lichens have a very slow growth rate.

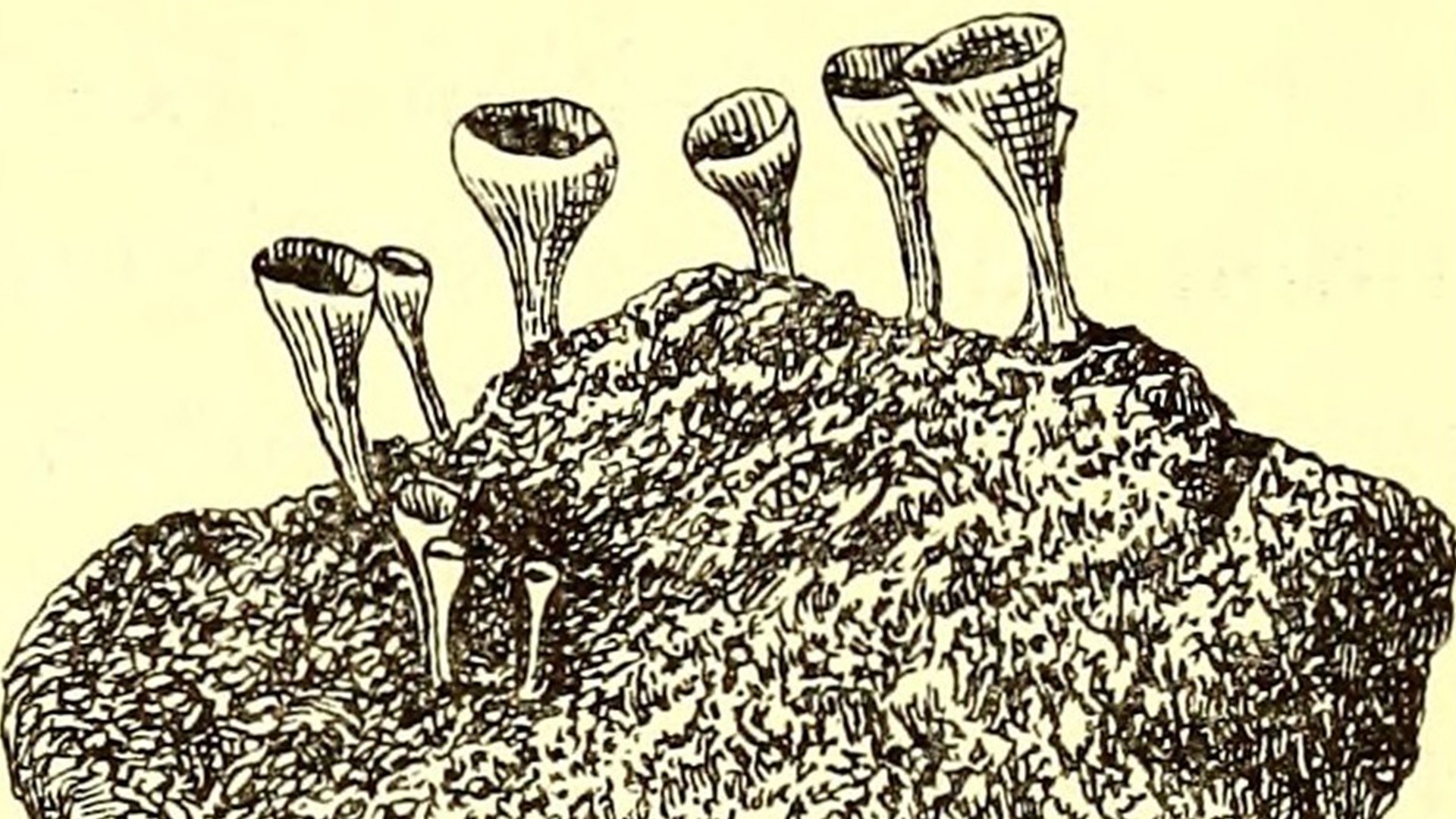

The squamulose lichen Devil’s Matchstick (Cladonia floerkeana)

Carnival microbe

Lichens are a highly striking presence in nature. They include crustose, foliose, squamulose, fruticose, filamentous and gelatinous lichens in virtually every colour of the rainbow. This dazzling variety of colours and shapes has inspired people to invent the strangest names for lichen species. Some examples are the Smooth Horn Lichen (Cladonia gracilis), the Humble Pixie-Cup Lichen (Cladonia humilis), the Split-peg Pixie-Cup Lichen (Cladonia cariosa) or the String-of-Sausage Lichen (Usnea articulata).

The squamulose Humble Pixie-Cup Lichen (Cladonia humilis)

Pioneers

Lichens grow very slowly, so they fail to thrive in locations where plants are able to take root. Instead, they prefer places where plants struggle, such as stones or roof tiles. Extreme circumstances including cold, warmth and drought are favoured by lichens as well. In fact, Reindeer Lichen or Reindeer Moss (Cladonia rangiferina, not a moss but a lichen) is the key source of food for reindeer living on the cold tundra of Lapland.

Mosses and lichens can be found in similar locations, both growing in mats, filaments or tufts. The main difference is that mosses belong to the plant kingdom, while lichens are a symbiotic life form of microbes.

Fishbone Beard Lichen (Usnea filipendula).

Varied uses

Not only reindeer use lichens; people have done so for ages as well. Brownish-green squamulose lichens of the Roccella fungus have been used for dyeing clothes since the 18th century. The reason is that Roccella turns red when mixed with an acid (originally urine). Adding a base (such as calcium) will turn Roccella blue. If you remember your chemistry lessons, you will have recognised these colour codes from litmus paper. To this end, scientists later used Roccella as an indicator to find out whether a liquid is an acid or a base.

It has also served as a medicine. Lichens have been applied to cure a wide range of illnesses over centuries. For example, the lichen of the Peltigera fungus has been used against rabies, while Iceland Moss (Cetraria islandica, which is again a lichen) has been prescribed against constipation. There is currently mounting scientific evidence for the medicinal properties of lichens. As lichens need to protect themselves against harmful bacteria in nature, some of them produce antibacterial substances. Scientists looking for new types of antibiotics are keenly interested in these substances.

Measuring instrument

Lichens are highly sensitive to a changing environment. Scientists discovered during the 1950s that there were far fewer species of lichen in urban areas than in rural areas. The reason turned out to be hydrogen sulfide from factory fumes, which is detrimental to lichens. It would still take nearly two decades until air quality could be demonstrated by another method. Before this moment, lichens were actually the only reliable instrument to measure air pollution. Lichens remain a good indicator of air quality until the present day.